Introduction

It’s not uncommon to hear claims that dietary protein eaten in excess of some arbitrary number will be stored as body fat. Even those who are supposed to be reputable sources for nutrition information propagate this dogma. These claims however tend to drastically ignore context. While paging through one of my old nutrition textbooks, I came across a section in the protein chapter regarding amino acids and energy metabolism [1]. To quote the book directly:

“[E]ating extra protein during times of glucose and energy sufficiency generally contributes to more fat storage, not muscle growth. This is because, during times of glucose and energy excess, your body redirects the flow of amino acids away from gluconeogenesis and ATP-producing pathways and instead converts them to lipids […] The resulting lipids can subsequently be stored as body fat for later use.”

(pg. 198)

This is, more or less, supported by another textbook I own [2]:

“In times of excess energy and protein intakes coupled with adequate carbohydrate intake, the carbon skeleton of amino acids may be used to synthesize fatty acids.”

(pg. 213)

While these passages do take into account the metabolic state of the person, I still find these explanations (the first one especially) to be lacking, even borderline misleading. Indeed, more recent evidence is needed when talking about amino acid conversion to fatty acids and subsequent body fat storage. While the metabolic pathways to convert amino acids to fatty acids do in fact exist, the reality of the matter is that under almost no circumstance will this ever happen. In all honesty, I have yet to actually find a convincing scientific example where this happens. So, without much further ado, what is to follow is the long explanation as to why you shouldn’t worry about protein getting stored as body fat.

Protein digestion begins in the stomach and ends in the small intestine

While the physical breakdown of proteins does take place in the mouth, it’s not until the protein reaches the stomach that appreciable chemical breakdown occurs; this is facilitated by hydrochloric acid (HCl) and the enzyme pepsin (converted from its inactive form, pepsinogen). Once the initial protein denaturing and peptide cleaving is complete, the product polypeptides pass through the pyloric sphincter of the stomach and into the proximal small intestine.

The proximal small intestine (the duodenum to be exact) is where most of the digestion of proteins and virtually all of the absorption of amino acids occurs (a very small amount do get excreted in the feces). Here even more digestive enzymes are present to break down the remaining polypeptides into their individual amino acids along with some trace amounts of di- and tri-peptides. Once broken down completely, the free amino acids and di-/tri-peptides can then enter the cells of the small intestine where some (especially glutamine) are used for energy within the intestinal cells, with the remaining passing through into hepatic portal circulation. Those that do pass into circulation are destined for the liver.

Protein absorption claims

Before we head on over to the liver and discuss amino acid metabolism with regards to the initial claims, I would first like to touch upon another related (or variant) claim that some of you may have heard in the lay media or from an uneducated classmate, etc. It usually reads:

“The average person can only absorb 30 grams of protein at one sitting. Anything above that will be stored as fat.”

Unlike the claims in the introduction, this one offers no context whatsoever. Moreover, it’s downright moronic. And while this sounds like straw man argument readily poised for the takedown, I actually got this gem of wisdom from an online article written by a Registered Dietitian. Believe me; I couldn’t make this crap up if I wanted to (note: this is not to slander the RD profession, this is just an example which happened to involve someone who should know better).

For instance, let’s take someone who eats, dare I say it, 40 grams of protein in one sitting. If we are to assume only 30g are absorbed at a time, then it’s safe to say that the extra 10g will be excreted in the feces. If this were the case, most people would be egesting tiny sirloin steaks on a daily basis. Nevertheless, based on the initial argument, how are you supposed to store 10g of excess protein as body fat if you can’t even (allegedly) absorb it in the first place? Most people (who I can understand don’t have an advanced degree in nutrition) don’t realize the difference between utilization and absorption and make this fundamental error. I’m not quite sure what this woman’s excuse is, because in order to store or metabolize a nutrient (i.e. utilize it), it must first be absorbed into the body.

The bottom line is that your GI tract will take its sweet time absorbing protein, no matter the amount. Thirty grams is just an arbitrary number that has no roots in scientific evidence. For a more complete and in-depth review of this topic, I suggest reading a rather recent article by my friend and colleague, Alan Aragon.

At this point let us circle back to the initial claim, that excess protein, which has already been absorbed, during times of adequate energy and carbohydrate intake, is converted to fatty acids and stored as body fat.

Liver, the primary site for amino acid metabolism

As we’ve already covered, the amino acids released from the small intestine are destined for the liver. Over half of all the amino acids ingested (in the form of protein) are bound for and taken up by the liver. The liver acts almost as a monitor for absorbed amino acids and adjusts their metabolism (breakdown, synthesis, catabolism, anabolism etc.) according to the body’s metabolic state and needs [2]. It is here the initial claim comes into play. While the pathways for fatty acid synthesis from amino acids do exist, no argument there, the statement that all excess protein, under specified conditions, will be stored as fat ignores recent evidence.

[Enter one of the most tightly controlled studies of our time]

Bray GA, et al. 2012

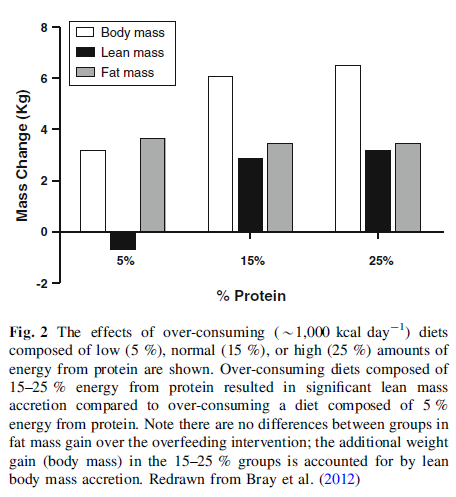

In 2012, George A. Bray and colleagues [3] sought to examine whether the level of dietary protein affected body composition, weight gain, and/or energy expenditure in subjects randomized to one of three hypercaloric diets: low protein (5%), normal protein (15%), or high protein (25%). Once randomized, subjects were admitted to a metabolic ward and were force fed 140% (+1,000kcals/day) of their maintenance calorie needs for 8 weeks straight. Protein intakes averaged ~47g (0.68g/kg) for the low protein group and 140g (1.79g/kg) and 230g (3.0g/kg) for the normal and high protein groups, respectively. Carbohydrate was kept constant between groups (41-42%), with dietary fat ranging from 33% in the high protein group to 44% and 52% in the normal and low protein groups, respectively. Lastly, during the course of the 8-week overfeeding period, subjects’ body composition was measured bi-weekly using dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA; i.e. the “Gold Standard” for measuring body composition).

Results

At the end of the study, all subjects gained weight with near identical increases in body fat between the three groups (in actuality, the higher protein groups actually gained slightly less body fat than the lower protein group, however, this wasn’t significant). The group eating the low protein diet gained the least amount of weight (3.16 kg) with the normal and high protein groups gaining about twice as much weight (6.05 and 6.51 kg, respectively). See the chart below.

However, as you can see, the additional ~3 kg of body weight gained in the higher protein groups (15% and 25%) was due to an increase in lean body mass and not body fat. To quote the conclusions of the authors:

However, as you can see, the additional ~3 kg of body weight gained in the higher protein groups (15% and 25%) was due to an increase in lean body mass and not body fat. To quote the conclusions of the authors:

“Calories alone […] contributed to the increase in body fat. In contrast, protein contributed to changes in […] lean body mass, but not to the increase in body fat.”

While we can’t say for sure the exact composition of the lean mass that was gained, we can assuredly say that the extra protein was not primarily used for fat storage. My hunch is that the protein was predominantly converted to glucose (via gluconeogenesis) and stored subsequently as glycogen with the accompanying water weight. Either way, it wasn’t body fat.

Regroup

So before we continue, let’s just take a second for this sink in. These subjects were literally forced to eat ~1,000kcals more than what they needed to maintain their body weight for 8 full weeks (not an easy task for even the strong willed) and even then it was seen that the protein contributed to increases in lean body mass rather than body fat. Given the initial claim – that once energy, glucose and protein requirements are met all excess amino acids will get converted to fatty acids and stored as body fat – I find it hard to argue that those in the higher protein groups did not meet any of the aforementioned requisites. In reality, they far and away surpassed them, yet still did not gain additional body fat compared to the lower protein group. This is in stark contrast to what is traditionally thought.

In the end, however, we’re still left with the quintessential question underlying the entire concept, and that is: what is the maximal amount of protein (amino acids) that the body can effectively utilize before being converted to fatty acids and stored as body fat? Given the results of this study it appears that; this number is either way higher than three times the current RDA with concomitant hypercaloric intakes for weeks on end, or; it requires a similar overfeeding protocol drawn out over a longer period of time (i.e. greater than 8 weeks) at which point lean mass gains would most likely plateau and fat mass would accrue. Either way, both situations are highly unlikely in the general public and even those consciously trying to gain weight with higher intakes of protein and calories. Moreover, this upper extreme is likely to be highly individual and contingent upon other factors such as genetics, lifestyle, training status (if an athlete), etc. Unfortunately, we just don’t have the answers to these questions right now.

Conclusions

So, while we do biochemically possess the pathways needed to convert amino acids to fatty acids, the chances of that ever happening to a significant degree during higher protein intakes, even in the face of adequate energy and carbohydrates, are irrelevant given what we know about the extreme measures that need to be surpassed in order for any appreciable fat gain from protein to take place.

Indeed, overeating by ~1,000kcals/day for 8 weeks in combination with higher protein intakes did not amount to any additional gains in body fat compared to a lower protein, hypercaloric diet. Rather, excess protein in the face of overfeeding actually contributed to gains in lean body mass (be that what it may); quite the contrary to what textbooks and classrooms teach. In reality, the chances that excess protein contributes to body fat stores are insignificant, and arguably physically impossible under normal and/or reasonable hypercaloric conditions that most people/athletes might face on a daily basis. Only until theoretical extremes, either for protein intakes or calories or both are achieved, will there be any significant contributions to body fat from excess protein intake. This shouldn’t concern most people in the slightest.

References

1. McGuire M, Beerman, KA.: Nutritional Sciences: From Fundamentals to Food. 2nd edn. Belmont, CA.: Wadsworth Cengage Learning; 2011.

2. Gropper S, Smith, JL., Groff, JL.: Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism. 5th edn. Belmont, CA.: Wadsworth Cengage Learning; 2009.

3. Bray GA, Smith SR, de Jonge L, Xie H, Rood J, Martin CK, Most M, Brock C, Mancuso S, Redman LM: Effect of dietary protein content on weight gain, energy expenditure, and body composition during overeating: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012, 307:47-55.

Great article, Dylan.

Thanks Bill, glad you liked it and thanks for sharing.

This question it seems must take insulin levels into account as the fat storing hormone.

The chart shows that the relation between protein intake and lean mass gain is not linear. At some point, incremental increases in protein intake no longer result in significant increases in lean mass. I find this to be the most interesting part of the article. But I’m still not clear (convinced) about what is happening to the protein that does not contribute to lean mass gain.

Pingback: 22 “LOCO” Good Articles and Videos | Dynamic Duo Blog Site

After going through tons of online information about excess protein and body fat, your piece gave the most convincing answer. Thanks for this research.

Thank you for this, and the references.

I think we have a societal misconception that weight gain, especially in the out of shape, is always fat. That has never been true. Some of the weight gain is also going to be meat, or what you term “lean body mass.” If you have no muscle tone, the meat will hang just like fat.

I don’t think there is any such thing as a person who can walk and talk and stand upright who has zero muscle tone.

I think you might have overlooked a little something here, not that it makes you wrong. Your statement:

“My hunch is that the protein was predominantly converted to glucose (via gluconeogenesis) and stored subsequently as glycogen with the accompanying water weight. Either way, it wasn’t body fat.”

It is my understanding (correct me if I’m wrong) that when a body has a lot of glucose to store, it’ll convert it to glycogen first and stash it in the muscles and the liver. Once the glycogen is topped up, it’ll begin storing any more excess glucose as fat.

So maybe what’s going on here, and what people are seeing as “excess protein converted to fat,” is actually “excess protein converted to glycogen which eventually forces the body to go directly to storing excess glucose as fat.”

Carbohydrate is the least necessary macronutrient so if you’re going to gorge yourself on meat all day long, maybe you want to skip the starchy and sugary accompaniments to avoid the fat gain.

(Not that there is anything wrong with eating meat all day long! I’m just saying.)

Dana,

You are correct in your line of thinking. My point is that, for amino acids –> glucose –> fatty acids to happen (or amino acids –> fatty acids), one must eat an extreme diet that most people don’t/could not eat even if they tried. As the Bray study suggests, protein in excess mostly leads to increases in lean mass (muscle, glycogen, water content) and very little to fat mass.

I’ll re-post my relevant comments from the article, here:

“In the end, however, we’re still left with the quintessential question underlying the entire concept, and that is: what is the maximal amount of protein (amino acids) that the body can effectively utilize before being converted to fatty acids and stored as body fat? Given the results of this study it appears that; this number is either way higher than three times the current RDA with concomitant hypercaloric intakes for weeks on end, or; it requires a similar overfeeding protocol drawn out over a longer period of time (i.e. greater than 8 weeks) at which point lean mass gains would most likely plateau and fat mass would accrue. Either way, both situations are highly unlikely in the general public and even those consciously trying to gain weight with higher intakes of protein and calories. Moreover, this upper extreme is likely to be highly individual and contingent upon other factors such as genetics, lifestyle, training status (if an athlete), etc. Unfortunately, we just don’t have the answers to these questions right now.”

Your conclusions of this study are off. Few important points you missed:

1) Those on the low protein diet were only eating 47g of protein per day, not even getting the RDA for men of a normal weight of 56 g/day (0.8g/kg). Thus this is why we saw a decrease in lean mass and failure to gain any additional muscle.

2) The researcher’s conclusion of the study is, “The key finding of this study is that calories are more important than protein while consuming excess amounts of energy with respect to increases in body fat.” Your leap that this study somehow shows that protein is not converted to fat is incorrect. If enough protein is consumed to meet the person’s daily needs, excess protein is converted to glucose/fat. Proteins are calories.

3) You fail to explain what happens to the excess protein when we eat it. You claim it is not just converted to glucose/lipids in the liver but do not say what happens. Does it automatically build extra muscle? If this was the case, then those on high protein diets (40%+) would put on lbs of muscle without exercise, but they don’t. Where does the excess protein go? Oh right, we know the answer, our livers convert it to glucose/lipids.

4) A better study to reference to support your conclusion would show the fate of excess protein consumed. There are many studies that do show it is turned into glucose. A few for your reference: http://jn.nutrition.org/content/133/6/2068S.long http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11079744

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1557428

5) Another point, the RD you reference is correct. “Rates of amino acids from the gut can vary from 1.4 g/h for raw egg white to 8 to 10 g/h for whey protein isolate.” According to this study http://home.exetel.com.au/surreality/health/A%20Review%20of%20Issues%20of%20Dietary%20Protein%20Intake%20in%20Humans.pdf

Richard,

Thank you for your reply. I will re-state your points with my responses to follow:

“Those on the low protein diet were only eating 47g of protein per day, not even getting the RDA for men of a normal weight of 56 g/day (0.8g/kg). Thus this is why we saw a decrease in lean mass and failure to gain any additional muscle.”

I agree completely. Not sure how this is relevant, though?

“The researcher’s conclusion of the study is, “The key finding of this study is that calories are more important than protein while consuming excess amounts of energy with respect to increases in body fat.” Your leap that this study somehow shows that protein is not converted to fat is incorrect. If enough protein is consumed to meet the person’s daily needs, excess protein is converted to glucose/fat. Proteins are calories.”

To your second point: I believe I mentioned that the extra protein (amino acids) are converted to glucose and stored as glycogen. Perhaps you should re-read the article? Furthermore, given the RDA of 0.8g/kg and the fact that those on the higher protein intakes were consuming 2x and 3x more, I would suggest that these persons were more than consuming their daily needs, YET they did not deposit more fat than the group who ate below the RDA for protein. Again, while some of the protein was assuredly used to make muscle, the rest was most likely converted to glucose and stored as glycogen. Yes, some amino acids (leucine in particular) probably did sneak in as a fatty acid here and there, but it’s not significant as the higher protein groups did NOT get more fat.

“You fail to explain what happens to the excess protein when we eat it. You claim it is not just converted to glucose/lipids in the liver but do not say what happens. Does it automatically build extra muscle? If this was the case, then those on high protein diets (40%+) would put on lbs of muscle without exercise, but they don’t. Where does the excess protein go? Oh right, we know the answer, our livers convert it to glucose/lipids.”

Again, you’re saying I claimed something that I did not claim. I explicitly mentioned that I believe it was converted to glucose and stored as glycogen. While I suggest you actually read my article, I’ll paste, here, what you obviously missed:

“While we can’t say for sure the exact composition of the lean mass that was gained, we can assuredly say that the extra protein was not primarily used for fat storage. My hunch is that the protein was predominantly converted to glucose (via gluconeogenesis) and stored subsequently as glycogen with the accompanying water weight. Either way, it wasn’t body fat.”

“Another point, the RD you reference is correct. “Rates of amino acids from the gut can vary from 1.4 g/h for raw egg white to 8 to 10 g/h for whey protein isolate.”

The RD I quoted is unequivocally wrong. How do you store the extra amino acids (over 30g) as body fat if you can’t even allegedly absorb them in the first place? Also, you’re giving me a rate (which I agree with) while she gave me an absolute number that completely disregards context. How can you claim she’s correct?

Brilliant article! Thank you. I coached amateur bodybuilders at the highest levels of NPC for more than a decade and this is the best article I’ve seen to date about protein consumption and the alleged “30g absorbed…then everything else to fat” fallacy.

Pingback: Can excess protein get stored as bodyfat? Pt. 2 | Calories in Context

Here is another study that seems to prove your point. This time its 4,4 gr/kg/d. http://www.jissn.com/content/pdf/1550-2783-11-19.pdf

Someone is plagiarizing someone because there are exact wording sentences and paragraphs when comparing yours to the following T-Nation article.

http://www.t-nation.com/diet-fat-loss/protein-will-not-make-you-fat

I don’t know who is in the wrong, but someone is.

Kent,

That’s because it’s the same article. T-Nation asked to re-post my article on their site with my permission. No harm done!

Pingback: Can Excess Protein Be Stored As Body Fat? Pt 1│NTW